Nina Simone: Defined by her goddam contradictions

Nina Simone - and her music - defied easy summary. As new BBC documentary Nina Simone & Me with Laura Mvula pays tribute, BRIAN MORTON charts the extraordinary life and genre-defying music of the electrifying performer responsible for such timeless classica as My Baby Just Cares for Me and Mississippi Goddam.

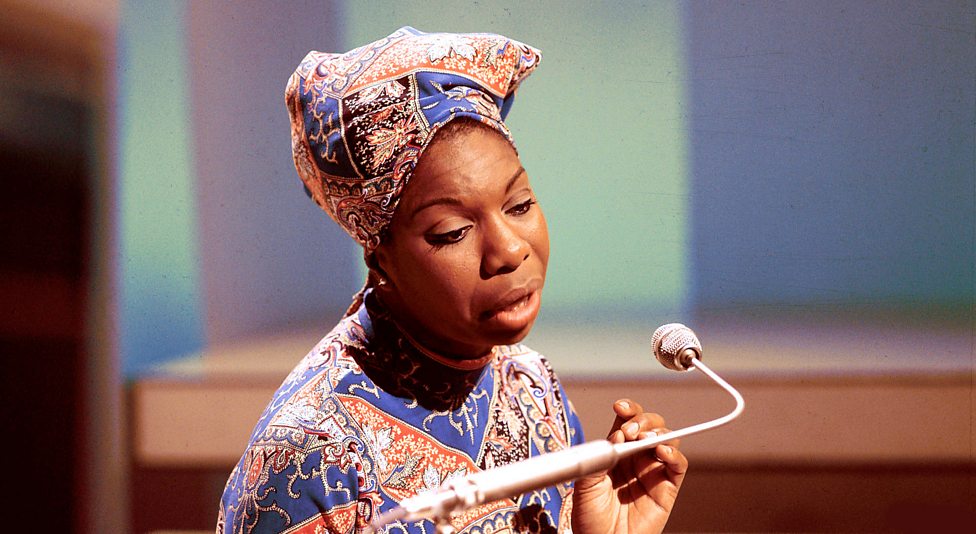

Credit: David Redfern/Getty Images

The boundaries of Nina Simone's hometown were set by picking a point near North Carolina's southern border and drawing a circle with a three-quarter mile radius.

Those who encountered her in later years sometimes felt that a like perimeter was called for when dealing with the famously turbulent singer and pianist.

Simone continued to regard herself as a classical performer

Others found that there was a deep philosophical calm at the eye of the storm, as long as one remembered to address her as “Dr Simone” and avoided what became a familiar list of off-limit questions and assumptions.

Many of them had to do with what kind of musician Simone was. Reference books have her down as 'jazz', 'soul', 'gospel', 'r'n'b', 'folk'; one brave soul heads up the Simone CV with 'cabaret singer'. None of these is utterly wrong, but none in isolation is right either.

Simone continued to regard herself as a classical performer, pointing to Bachian counterpoint as a defining characteristic of her work. Sharper-eared listeners will hear elements of canon and fugue alongside the blues and vernacular song.

Classical music should, perhaps, have been her destiny. A child prodigy, she might easily have taken the concert stage as Eunice Kathleen Waymon, but for the inconvenient fact of her skin colour.

One can say that while Eunice was born at 33 E. Livingston Street in Tryon, NC, Nina Simone was born on the steps of the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, the day that august institution turned her down as a student. Though Simone later studied at Juilliard, the rejection was brutal and unforgiven, and it transformed her life at a stroke.

The wayward behaviour of later years, a stormy passage of no-shows and walkouts, was routinely attributed to alcohol abuse, but while drink undoubtedly played a part it was merely the fuel to a deep inward contradiction that later lead to medication for schizophrenia.

No psychiatric diagnosis is more complex and loaded. It might be argued that Simone was not mentally ill but simply dealing with a profound divide in her cultural positioning: a deeply intuitive artist of world renown, ghettoised as a 'black' performer, authenticated by rage and intoxication, excluded from the echelons of creative probity that would have received her gladly had she been of almost any other race.

Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images.

It was a divide that turned her into an electrifying performer, the fierce voice of “Mississippi Goddam”, the magnificently alienated singer of “Central Park Blues” (both her own compositions), and the cheated, disenfranchised creator of “My Baby Just Cares For Me” which in the 1980s in Britain became the theme tune of the new moneyed hedonism when it was used as an ad for Chanel No 5 and on the basis of that climbed into the higher reaches of the singles chart.

Little Eunice grew up in a church house. Her mother, a housemaid, was an ordained Methodist minister; her father worked as a handyman, but sang and spoke in church as well. The music she first knew was church music.

Simone later said that her stage technique was that of a charismatic preacher, a form of “hypnosis”, in which repeated minor key vamps, held-back resolutions, implied cadences which took many minutes to emerge worked an audience into a state of furious expectation.

When later she began to miss gigs, the non-appearance was often as aesthetically powerful as the planned set, a perversity she acknowledged even though she never officially revealed the true reason.

Eunice Waymon became Nina Simone in the Midtown Bar in Atlantic City (she liked the first name, originally niña, and apparently took the second from a movie poster, presumably one starring Simone Signoret) and it was there that Bethlehem Records discovered her.

Bethlehem Records was a label that covered the waterfront stylistically, with jazz, soul, r'n'b (in the old sense) and even gospel-influenced acts on its books, so it was a logical destination for the newly emergent singer/pianist.

Simone recorded Little Girl Blue, whose title song was a so-called quodlibet of a Rodgers & Hart song and “Good King Wenceslas”.

The supposedly makeweight song on the album, which also went out as Jazz As Played In An Exclusive Side-Street Club, was “My Baby Just Cares For Me”. Simone sold her rights for $3,000, just the first of a series of poor business decisions that left her constantly out of pocket.

Simone later said that her stage technique was that of a charismatic preacher

In 1957 Bethlehem issued Nina Simone And Her Friends (subtitled with impressive lack of irony) as “an intimate variety of vocal charm”, using left-over tracks from the previous record and song performances by Chris Connor and Carmen McRae, who were also leaving the label. Asked if they were, indeed, friends, Simone answered with what used to be called an old-fashioned look.

Her own most distinctive contribution to the album was the instrumental “African Mailman”, a reminder that she was a pianist first and singer second. She moved after this to Colpix and remained there for eight records, punctuated by personal storms and a growing commitment to the civil rights movement, which later saw her marching with Martin Luther King jr and attracting the almost de rigueur interest of the FBI.

Simone's repertoire grew in proportion to her audience and reputation. “Black Is The Color Of My True Love's Hair” was the surprise lead-off item on her 1959 Town Hall album. Future recordings caught her at Carnegie Hall (a moment of bittersweet revenge against the Curtis board) and at the Newport Jazz Festival.

In 1962, she beat Bob Dylan to “House Of The Rising Sun”. Producers like Hecky Krasnow and Cal Lampley allowed her to combine traditional material with more elaborate settings and arrangements, though the lush With Strings was only released without her knowledge after she left Colpix. Folksy Nina used extra material from Carnegie Hall and included another intriguing quodlibet in “You Can Sing A Rainbow”/”Mighty Lak A Rose”.

When “Mississippi Goddam” was released in the first chastened spring after Dallas and in the warm-and-chill of Lyndon Johnson's “Great Society” experiment, Simone announced between verses that the song was a showtune for which the show hadn't yet been written.

She was unclear in later years whether she was optimistic or not about the chances of genuine cultural enfranchisement for African-Americans. Later years saw her leave the country - like Richard Wright and James Baldwin before her - for that traditional resort of exiles, France.

She died, surrounded by friends, at Carry-le-Rouet, near the mouth of the Rhône, just two months after her 70th birthday in 2003.

Another six years beyond her biblical span would have shown her a black man, a rainbow American, in the White House, but whether Simone would have been any more comfortable in Barack Obama's America than she was in Eisenhower's or Nixon's is open to question.

Like the country she represented and left, she was without category and defined by contradiction. It can be heard in every bar she played.

No comments:

Post a Comment