The pictures were taken for science, but found a wider audience

because they’re gorgeous and a little trippy.

Sam Droege really loves bees. He thinks they’re cute, for one thing. (Just look at that wee proboscis, those dangly antennae, and those compound eyes, wider and more open than a doe’s.) He can’t get enough of them and, at times, his enthusiasm gets the better of him. “I would argue, as would many other beeologists,” he says, “that most bees are arguably cuter than most kids.”

It’s hard to tell if he’s joking. But Droege’s job at the United States Geological Survey (USGS) is part-science and part–public relations. His clients are the bees, and he’s on a mission to persuade humans to love them as much as he does.

Droege is a wildlife biologist at the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center in Maryland, where he is developing a program to inventory and monitor North America’s native anthophiles. Some of his duties involve fieldwork, which he enjoys so much that he describes a trip to analyze the bee fauna in South Africa’s Kruger National Park as a “vacation.” “I can’t think of anything that feeds my spirit more,” he says, “than to be doing uninterrupted natural history in a warm, sunny, bee-filled part of the world while others endure snow up north.” Fair enough. Even if you never trek along with him, Droege will do his darnedest to convince you that bees pausing above the dry landscape’s flowers are just as worth swooning over as the pride of lions stalking past.

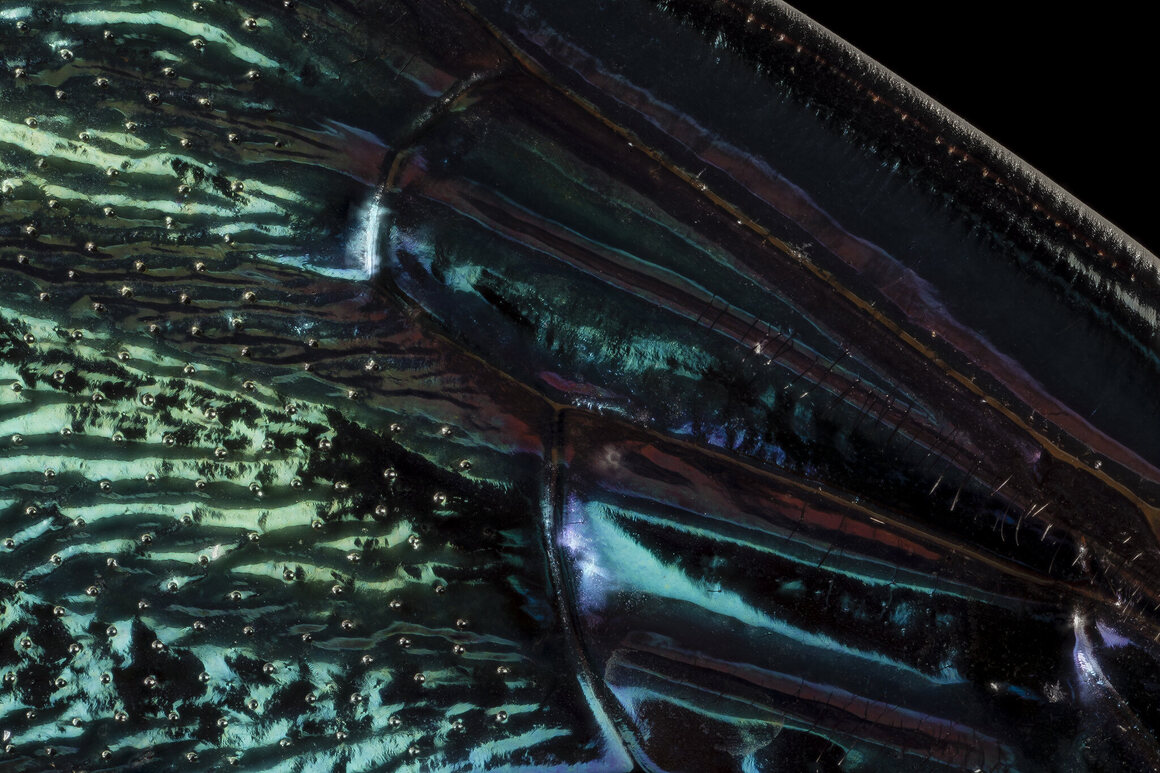

For that, he turns to Flickr, where he has mastered the unsubtle art of hype. Droege has shared thousands of photos from the USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab, mostly portraits of specimens posed against inky black backgrounds. This makes the insects’ features easy to observe and document, but it also looks badass, evoking glamorous portraits of rough-and-tumble rockstars, or a still life of luxury handbags in a glossy magazine. Each photo is accompanied by tidbits of information about the subject’s appearance and habits—as well as, often, a bit of bucolic verse by Emily Dickinson and an old-school emoji that looks a little like a bee’s head. Nearly 800 of Droege’s favorite shots are compiled in an album he calls “Eye Candy.”

Even when the images and captions are playful, they’re all in service of science—or describing its limits. Take the case of a little male bee from the genus Mourectotelles. “What an attractive bee,” Droege writes in the caption. “Unfortunately, that is about all we can say about this species, other than it is found in the western temperate regions of South America” (this individual hails from Argentina, specifically). Since the insect hasn’t yet been sorted into a specific species, Droege has dubbed him “Bee cute furry face.” This name, and other goofy ones like it, are internal placeholders for Droege and his colleagues, but used “sometimes as a way to indicate the essence of the species we are portraying,” he says. “It is mostly an accident that anyone runs into our hidden nomenclature.”

If someone does fall for those charms, it could pay off. As one might expect, research has found that the more likable a species seems, the more enthusiastic people are about conserving it. Overall, people seem to feel pretty okay about bees, according to a 2017 study in PLOS One. For that work, German researchers surveyed 499 students and 153 beekeepers, and found that both novices and fans were on board with protecting bees—but that doesn’t necessarily mean that they know much about them. In another 2017 study, ecologists from Utah State University found that even people who wanted to preserve bee habitats, curb pesticide use, and shore up colonies against collapse were ultimately a little clueless about the insects. “In our recent survey, 99 percent of our respondents said bees are critical or important, yet only 14 percent were able to guess within 1,000, the actual number of bee species in the United States,” said lead author Joseph Wilson, a Utah State biologist, in a news release. “Most people estimated around 50 species of bees, while the correct number is about 4,000 known species.”

The glamour shots “reached an audience who would never read any of my papers,” Droege explains, and the photos attest to the dazzling diversity of bees—tiny, fuzzy, wide, long-nosed, emerald, aubergine. The photos have flitted across the internet, even landing on the r/woahdude subreddit, a home for images and audio “that make a sober person feel stoned, or stoned person trip harder.” The pictures are the hook, and once readers are snared, the captions remind us that bees and other familiar pollinators are just the tip of the biodiversity iceberg.

Laurence Packer, a melittologist (that is, a bee expert) at York University in Toronto who collected that “Bee cute furry face” specimen, points out that experts also struggle to keep them straight. When he gives identification quizzes to students and professors, he often finds that even people who have been working in the field for years are fooled by other insects that look like bees, and bees that look like other insects. “There are 20,355 described bee species, and nobody on the planet can recognize all of them, for fairly obvious reasons,” Packer says. There are way too many for a single brain to recall—and they’ll surely be joined by more bees that will be documented in the future.

Packer travels the world collecting species, and makes frequent jaunts to Argentina and Chile. (Droege occasionally tags along.) Sometimes, a region will be remote enough that Packer is fairly confident that nearly any species he finds will be unrecorded in the scientific literature. He collected some while driving down a mountain in the Atacama Desert, for example, in what he calls a “spectacularly weird” setting where a few patches of flowers gave way to a sea of sand, and a bunch of long, long-tongued, pale bees swarmed. Sometimes he’s not sure whether something has already been recorded until he compares the specimen against identification keys or performs DNA analysis. Packer’s lab has already found 200 or so species, and has another 150 manuscripts in the pipeline.

There’s plenty of academic work left to be done: Packer suspects that there are several thousand species that have yet to be collected and described. “Just in [Mourectotelles] alone exists dozens of graduate degrees, waiting for someone to explore this group’s life history,” Droege writes on Flickr. Public relations campaigns like Droege’s could help spark curiosity about them, and a willingness to pitch in to help them where they’re struggling. “If you don’t know something,” Packer says, “you can’t like it.”

“Bees have no voice,” Droege says. “I am glad to partially speak for them.”

No comments:

Post a Comment