an Italian Song That

Sounds Like English—

But Is Just Nonsense

In 1972, fascination with American culture spurred

an Italian showman to revive a medieval comic tradition.

BEFORE CHILDREN LEARN HOW TO speak properly, they go through a period of imitating the sounds they hear, with occasionally hilarious results, at least for their parents. Baby talk evolves into proto-words, so that “octopus” might come out as “appah-duece,” or “strawberry” as “store-belly.” But it’s not just children who ape the sounds of spoken language. There’s a long tradition of songs that “sound” like another language without actually meaning anything. In Italy, for example, beginning in the 1950s, American songs, films, and jingles inspired a diverse range of “American sounding” cultural products.

The most famous is probably “Prisencolinensinainciusol,” a 1972 song composed by legendary Italian entertainer Adriano Celentano and performed by him and his wife, Claudia Mori. The song’s lyrics sound phonetically like American English—or at least what many Italians hear when an American speaks—but are clearly total, utter, delightful nonsense. You really have to hear it to appreciate it.

“Prisencolinensinainciusol” fell under the radar upon release, but in 1973—once Celentano performed it on Italian public broadcaster RAI—the song topped charts in Italy, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands.

It was rediscovered across the pond in the YouTube age, when in 2010 boingboing’s Cory Doctorow described a video of the song as “one of the most bizzare videos found on the internet,” and the 72-year-old Celentano was interviewed for an episode of National Public Radio’s “All Things Considered.” “Ever since I started singing, I was very influenced by American music and everything Americans did,” Celentano said.

He wasn’t alone. After World War II, American culture started to exert its influence in many parts of Europe. The phenomenon was especially strong in Italy, where the arrival of American troops in Rome in June 1944 helped mark the country’s liberation from fascism.

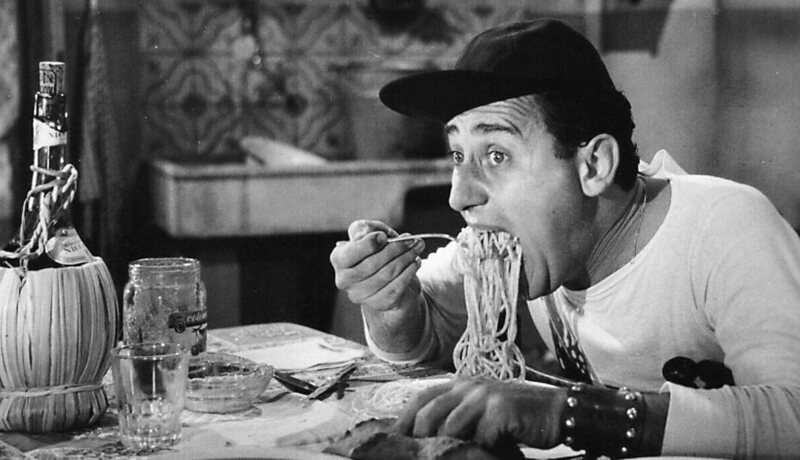

“Americanization” was captured in films such as 1954’s An American in Rome, in which Italian actor Alberto Sordi plays a young Roman who is obsessed with the United States. He seeks to imitate gli Americani in his daily life, and one of the most well-known scenes sees him trading red wine for milk.

By the time Celentano’s song came out, the sound of American English had been “contaminating” Italian culture for decades. Linguist Giuseppe Antonelli analyzed Italian pop songs produced between 1958 and 2007, and revealed the ways in which Italian singers have incorporated American sounds into their music.

One way was to use intermittent English words, with preference for trendy terms. The most notable example of this is “Tu vuo’ fa l’americano” (“You Want to Be American”), a 1956 song by Renato Carosone about a young Neapolitan who is trying to impress a girl.

The song, featured in the 1999 film The Talented Mr. Ripley, features mentions of “baseball,” “rock ‘n’ roll,” and “whiskey and soda,” which not only “sound American” but also evoke a kind of aspirational American lifestyle. Other songs alternated sentences in both languages, and still more, such as Bruno Martino’s 1959 “Kiss Me, Kiss Me,” were sung half in English and half in Italian.

Similarly, in the 1960s there was a trend of bands in England singing in Italian—with strong English accents. Both phenomena resulted in a similar hybrid sound, one that Italians responded to. According to Francesco Ciabattoni, who teaches Italian culture and literature at Georgetown University, this Anglo-Italian pop genre grew from Italy’s collective interest in America, as well as the British Invasion of the 1960s. “I am not sure how much thinking they put in it, but producers must have realized that imitating English and American sounds would sell more,” he says. Linguistics may have played a role, too. “The phonetic structure of English makes it more suited to rock or pop songs compared with Italian,” he adds.

“Rock or pop music is often arranged in ‘common time,’ a rhythmic pattern made of four beats with an emphasis on the second and fourth beat,” says Simone Lenzi, an Italian writer and frontman of Tuscan rock band Virginiana Miller. “That pattern goes very well with the English language, which is mostly made of short and monosyllabic words that can easily be arranged on four beats.” Italian, on the other hand, is mostly made of longer words—only about 2 percent of the most-used words are monosyllabic—making it more suited to arias than rock or pop. For example, Tracy Chapman’s “You got a fast car” translates as “Tu hai una macchina veloce.”

This isn’t to say that there’s not a wide range of popular music sung in Italian, but Celentano expressed his preference when he explained his creation to NPR. “So at a certain point, because I like American slang—which, for a singer, is much easier to sing than Italian—I thought that I would write a song which would only have as its theme the inability to communicate,” he said. “And to do this, I had to write a song where the lyrics didn’t mean anything.”

This isn’t to say that there’s not a wide range of popular music sung in Italian, but Celentano expressed his preference when he explained his creation to NPR. “So at a certain point, because I like American slang—which, for a singer, is much easier to sing than Italian—I thought that I would write a song which would only have as its theme the inability to communicate,” he said. “And to do this, I had to write a song where the lyrics didn’t mean anything.”

BUT THE ROOTS OF CELENTANO’S song go much further back than the end of World War II. “What Celentano is doing, inventing a nonsense language, was already done by Dante and by medieval comedians before him,” says Simone Marchesi, who teaches French and Italian medieval literature at Princeton University. And that practice, Marchesi explains, goes back even further, to the Old Testament.

Genesis 11:1–9 says that after the flood, the people of Earth, who all spoke the same language, founded the new city of Babel, and planned to build a tower tall enough to reach heaven. In reaction to this act of arrogance, God decided to confuse humans by creating different languages so that they could no longer understand each other.

Genesis 11:1–9 says that after the flood, the people of Earth, who all spoke the same language, founded the new city of Babel, and planned to build a tower tall enough to reach heaven. In reaction to this act of arrogance, God decided to confuse humans by creating different languages so that they could no longer understand each other.

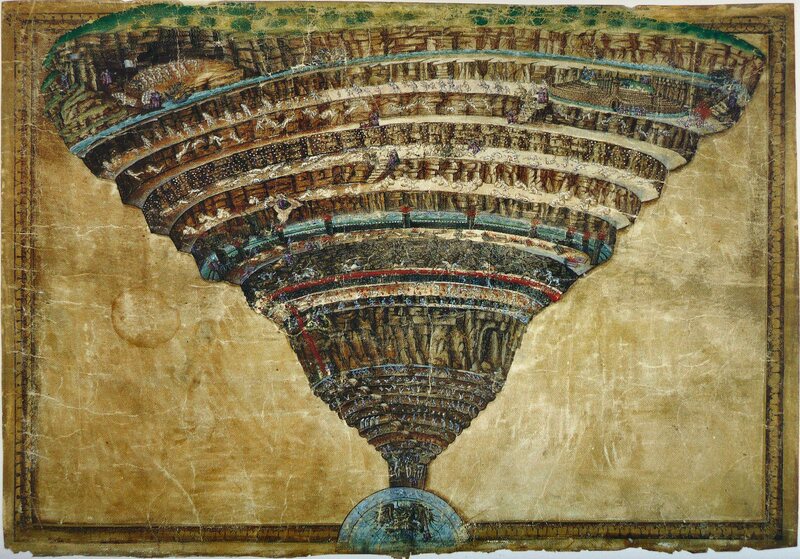

And so, in Dante’s Divine Comedy, the author encounters a giant named Nimrod next to the ninth circle of hell. In non-canonical writings, Nimrod is associated with building the Tower of Babel. He approaches Dante and Virgil, and says “Raphèl maí amècche zabí almi,” a series of words that has no meaning but, according to some scholars, can sound a little like Old Hebrew.

Virgil says, “every language is to him the same/as his to others—no one knows his tongue.” Nimrod speaks a failed language, and failed languages are the result of divine punishment. This is why, Marchesi explains, nonsense languages were traditionally associated with sin. “The medieval period was characterized by a division in ‘high’ aspects of life, associated with the heavens, and ‘low’ aspects associated with carnal, animal existence: the realm of sin.” For language, the high part was “signifiers”—the concepts that language conveys—and the low part was the “signs”—the sounds and symbols that represent those concepts.

It then follows that purely ideal, divine language requires no sound, which is how the angels of the Divine Comedy communicate. Lower language, on the other hand, would be rooted in the materiality of mortal sinners—pure sound. “And what happens when language becomes pure sound?” Marchesi says. “You need the body. It’s the language of mimics, it’s a language of performance.” Indeed, comedians and jesters in the Middle Ages resorted to invented sounds to tell bawdy, racy stories, and tales about hunger, disease, and other “low” subjects.

An example of this is Grammelot, a system of languages popularized by Commedia dell’arte, a theatrical form that started in Italy in the 16th century and later spread around Europe. Grammelot was used by itinerant performers to “sound” like they were performing in a local language by a using macaronic and onomatopoeic elements together with mimicry and mime. Dario Fo, an Italian playwright and actor who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1997, featured Grammelot in his 1996 show Mistero Buffo (Comic Mystery Play).

“Charlie Chaplin even did something like that,” Marchesi points out. The otherwise silent 1936 film Modern Times sees the comedian performing a song that sounds like a mix of Italian and French, but means absolutely nothing. “He sings about love, one can make sense of it through the performance, even if sounds do not make sense,” Marchesi says.

So a few millennia after Babel, a few centuries after Dante, and a few decades after Chaplin, Celentano offered his take on this classic performance trick. “When I first heard Celentano’s song I was very impressed by its ‘Americanness,’” says Arielle Saiber, a professor of Romance languages and literatures at Bowdoin College. “It notably emphasizes the American nasal, mumbling, drawn out sort of sounds … distinct from the clean ‘clip’ of British English or melodic Italian.”

Indeed, it seems like Celentano followed the advice on Grammelot that Fo offered in his book The Tricks of the Trade:

To perform a narrative in Grammelot, it is of decisive importance to have at your disposal a repertoire of the most familiar tonal and sound stereotypes of a language, and to establish clearly the rhythms and cadences of the language to which you wish to refer.

And Celentano certainly grasped the American rhythms and cadences of the 1960s. “Celentano captured stereotypical American sounds of that time, from movies and rock songs, much in the way that comici dell’arte, comedians of Commedia dell’arte theater, in the 1600s imitated colloquial, regional language,” Saiber says.

Of equal importance, Fo adds, is to inform the audience of what the Grammelot performance will be about. So in his 1972 television performance, Celentano introduces “Prisencolinensinainciusol” as the one word that can express universal love. If these rules are followed, Fo writes, the imaginary world created by the performer will make perfect sense for that audience in that time and place.

So, does prisencolinensinainciusol make any sense to you?

So, does prisencolinensinainciusol make any sense to you?

No comments:

Post a Comment