|

| June 28, 2023 |

A photo of a 15-year-old Manuel M. Moreno in the March 29, 1925, edition of the Junior Times, the children's supplement of the Los Angeles Times. (Los Angeles Times) A photo of a 15-year-old Manuel M. Moreno in the March 29, 1925, edition of the Junior Times, the children's supplement of the Los Angeles Times. (Los Angeles Times) |

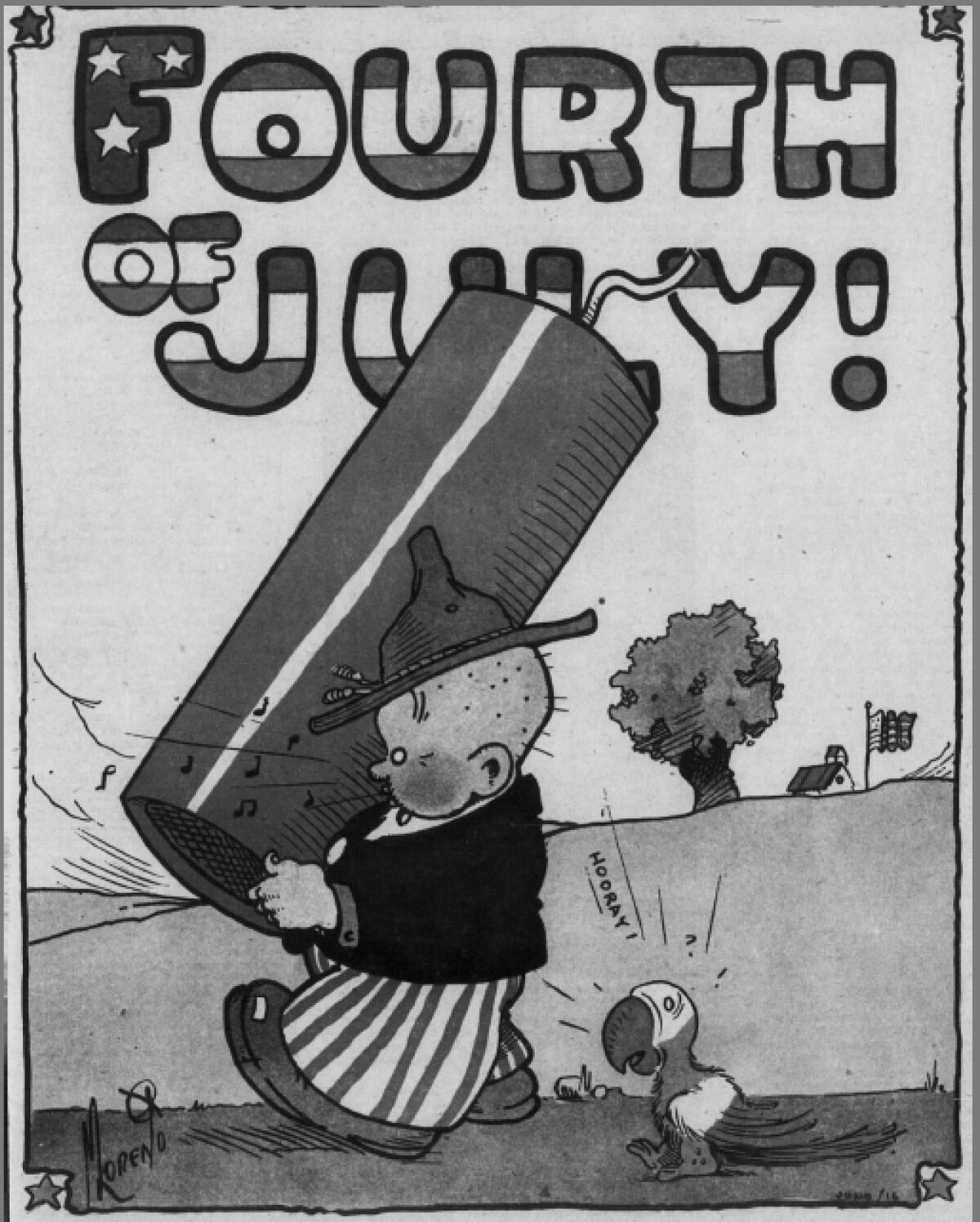

By Gustavo Arellano Good morning, and welcome to the Essential California newsletter. It’s Wednesday, June 28. I’m Gustavo Arellano, reporting from Orange County. I’m a columnist, which means I’m allowed to have opinions. Like: Animation is cool. My late mami always said that I learned English as quickly as I did by watching classic cartoons: Mickey Mouse, Tom & Jerry, Bugs Bunny, Woody Woodpecker, Mighty Mouse and so many more. As a teen through my early 20s, my favorite shows were FOX must-sees “The Simpsons,” “King of the Hill” and “Futurama.” My adult years brought on “South Park,” “SpongeBob SquarePants” and most anything on Cartoon Network, and the streaming era has been all about “BoJack Horseman” and “Tuca & Bertie.” From early on, I noticed something interesting: a lot of Hispanic surnames in the credits. While Old Hollywood stereotyped Latinos or just ignored them (still does, alas), animation was a space where Latinos — particularly Mexican Americans — were able to flourish. Some became legends like Bill Melendez (who brought “Peanuts” to television), Phil Roman (whose animation studio long produced “The Simpsons”) and Disney stalwart X Atencio; others might not get as much mainstream attention but are nevertheless respected by animation buffs. In the latter group is Manuel M. Moreno. He was a trusted supervisor for Walter Lantz in the 1930s, and also worked for MGM. Disney animators who had worked with Moreno tried multiple times to recruit him to the Mouse House, but he instead took over his brother’s camera shop during World War II, then moved to his native Mexico to run an animation studio. Moreno returned to L.A. in the 1950s, left the world of cartoons, and ran a successful photo-processing store for decades. Loyola Marymount animation professor Tom Klein is working on a biography of Moreno, whom he called “a figure who really deserved more and could’ve been so much more.” He plans to tell the history of animation in Los Angeles through his book, and has been in the proverbial salt mines for years. That’s how he found out that Moreno was probably the first Latino to pen his own regular comic strip in a major American newspaper, from 1924-26. The paper? The Los Angeles Times. Moreno did this as a teenager. What did you do in high school? “Despite the racism of the time, there’s also a moment where everyone thinks they can get a piece of the American dream,” Klein told me. “And here’s this kid taking advantage of getting exposure in the L.A. Times, and he succeeds.” Moreno’s relationship with this paper began 100 years ago this week, when the July 1, 1923, edition of the Junior Times (our children’s supplement) back then published three of his illustrations: a newsboy, two soldiers and a fisherman falling off his boat while pulling in a giant catch. Aunt Dolly, the pseudonym for the head of the Junior Times, praised the 13-year-old Moreno for having “never given up hope” of getting published. “I can imagine the kind of man you’ll be, one of those fellows who make things come their way,” she wrote, “and believe that opportunity is manufactured of ourselves, not brought about by circumstance and chance.” A year later, Moreno was writing and inking an occasional comic strip under the title “The Tuttlems,” the travails of a husband and wife. He also frequently illustrated the front page of the Junior Times, an honor that came with a $10 bonus — about $177 in today’s money. His big break, however, was with “Keen and Feeble Tat,” two brothers who constantly got into pickles and which the Times published weekly. By then, the paper already hailed him as “one of our most consistent winners of art prizes.”  July 4, 1926 illustration by then-16-year-old Manuel M. Moreno that appeared in the front page of the Junior Times, the L.A. Times’ children’s supplement (Los Angeles Times) “He looks like a child cartoonist when he first starts,” Klein said of Moreno, “but his level of talent accelerates so quickly that by the end of his run, he’s drawing at a professional level.” The professor praised the teen’s quick pivot to “continuity strips” — a story told over weeks — instead of one-off gags, citing a run where Keen and Feeble Tat fly to different countries. “Manuel has not traveled the world, but he’s reading and illustrating it,” Klein added. “Already, you have the notion of a child who sees all the possibilities in the world, and he seems fearless.” Moreno’s last illustration for the Times published in 1927, but he never abandoned the paper that gave him his break. “Manuel is now making a good salary, but has he forgotten us?” Aunt Dolly wondered that year. “Never has he missed a club art meeting, nor has he lost the gentleness and kindness that have always stamped him as a clean-cut sport.” The following year, the Times reported that Moreno held a screening of some of his “animated funnies” to members of the Junior Times Club. By then, the 19-year-old already worked for animation studios. Moreno’s torch for Latino representation in the Times was being carried by another young Mexican immigrant: Alex Perez, who also started at the Junior Times before becoming a staff illustrator for the adult Times for 50 years. Klein has authored articles on Moreno for the online publication Cartoon Research and stresses his career isn’t really a what-if, since Moreno found success. But the scholar still thinks Moreno should be better known, and feels that fame would’ve come he had joined Disney. “Manuel would’ve been part of something that is celebrated around the world,” Klein said. “There’d probably be many books written about him. It’s like the talent that got away.” |

No comments:

Post a Comment