Good morning. It’s Friday, Nov. 3. Here’s what you need to know to start your day.

- Daylight saving time is ending and we want to hear from you

- Porter and Schiff may be headed for a runoff

- Why so many actors are launching their own businesses

- And here’s today’s e-newspaper

Should we not do the time warp again?

We’re two days away from our twice-yearly reminder that for most of the U.S. and roughly a third of the world’s nations, time is an illusion. Soon then will be now.

Daylight saving time (I’ll just call it DST moving forward) ends Sunday when we move our clocks back an hour into standard time. Then, in 19 weeks, the government says it’s actually one hour in the future (except for two states and U.S. territories) and we’ll go with that — at least at the social level — until we do the time warp all over again.

DST has been a thorn in our circadian side from the get-go. It began in Europe during WWI and was enacted in the U.S. in 1918, mainly as an effort to conserve fuel to aid the war effort. But business also backed the change, since it gave people an extra hour of daylight to shop. Through the rest of the 20th century, we adopted various forms of DST, extended it further into the year and even tried to make it year-round during the oil crisis in the ‘70s, though that experiment was short-lived.

And for as long as we’ve been tinkering with our social construct of time, people have been wondering why we do this and whether we should stop.

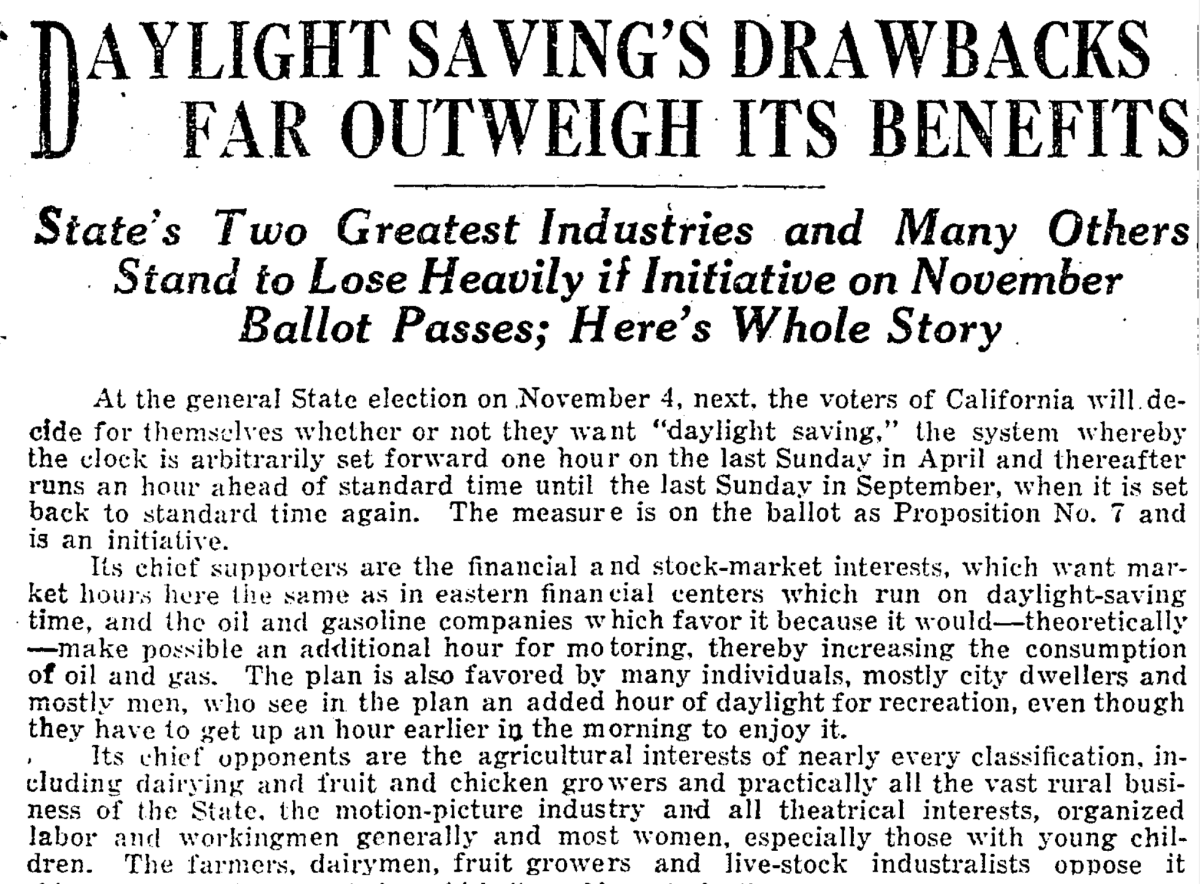

A Times article published Sept. 28, 1930 explains an upcoming ballot measure to enact DST in California and the debate over the time change. (Los Angeles Times archive)

Roughly a century later, we’re still giving ourselves jet lag without flying anywhere. Why do we still do this?

Because “no one can agree on exactly where to keep the time,” said Heinrich Gompf, a sleep researcher with UC Davis Health’s Department of Neurological Surgery.

I asked Gompf what’s happening at the neurological level and why our bodies tend to make it clear they don’t appreciate subjective time travel.

He said it comes down to our brains’ suprachiasmatic nucleus, “the master clock” that we each run on. It relies on sunlight — particularly morning light — to sync up to the world outside ourselves. Changing our clocks creates a mismatch, he explained, resulting in “internal tension between our internal clock and our external social calendar.”

The start and end of DST each affect our health, but Gompf pointed to research that springing ahead (the start of DST) is particularly harmful. People get less sleep, especially kids. There’s an uptick in heart attacks and strokes immediately following the change. Some studies show fatal traffic collisions also increase in the days after DST takes effect.

“The data are pretty clear that standard time is the one that’s better overall for human health,” he said. “And also, not changing the clock twice a year [is] better for human health.”

That’s why the American Medical Assn., the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and other major medical societies have called for the abolition of daylight saving time. But Gompf isn’t convinced U.S. legislators will ever agree on a set time — especially if the House can barely agree on picking a new speaker.

And the public’s stance on DST often comes down to individual preference — are you more of a night owl or an early bird? Do you place more value on the sun rising sooner or setting later? That preference runs deeper than any political ideology, Gompf noted.

“I personally wonder if a compromise could be reached whereby we just have less daylight savings time,” he said. “So that we switch about a month later in the spring and about a month earlier in the fall.”

“But I don’t ever see it going that way,” he added.

No comments:

Post a Comment