What did Cleopatra, Egypt's last pharaoh,

really look like?

Cleopatra VII may have been the most famous woman in the ancient world. She was the last of a dynasty that ruled ancient Egypt for around 300 years, from the death of Alexander the Great to the rise of the Roman Empire.

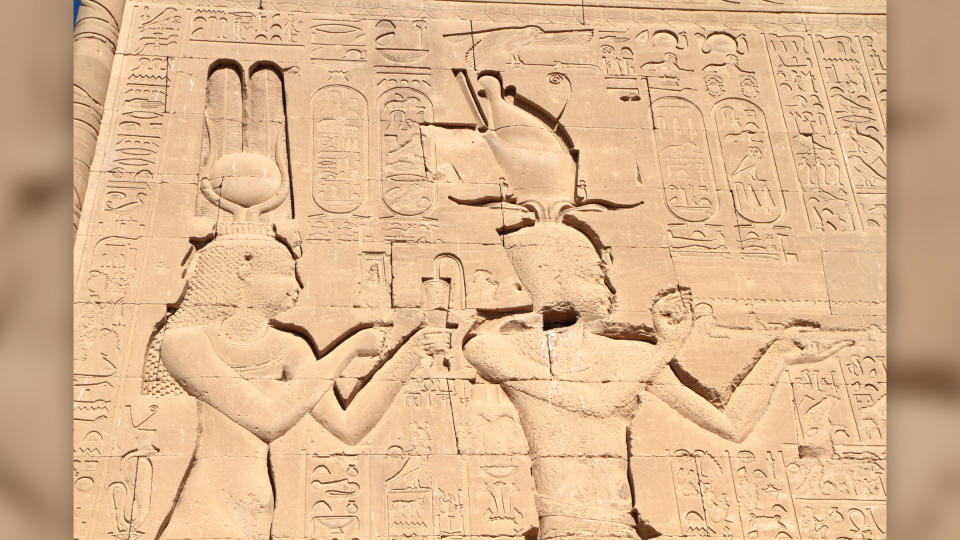

Her face has been immortalized on a handful of artifacts from the ancient world, including coins and a relief. Perhaps the best known depiction of her is a relief at Dendera temple in Egypt that shows her alongside her son Caesarion.

But despite these ancient depictions, we actually know very little about what the ancient world's most powerful woman looked like. In recent years, that controversy has centered on a contentious topic: What color was Cleopatra's skin?

The archaeological record doesn't leave us many clues, experts told Live Science. Her body has never been found, and depictions made at the time were likely not intended to be a true representation of her physical attributes.

"We simply do not have evidence from the ancient world that indicates Cleopatra's skin tone," Prudence Jones, a professor of classics and general humanities at Montclair State University, told Live Science in an email.

What's more, our conception of skin color as "white" or "Black" would have been foreign to the ancient people living at the time.

Cleopatra VII reigned from roughly 51-30 B.C. and was the last ruler of the Ptolemaic dynasty, which ruled Egypt for nearly 300 years. When Julius Caesar came to Egypt she had a son with him called Caesarion. Later she had a romance with Mark Antony which resulted in the birth of three children. After the forces of Octavian conquered Egypt in 30 B.C. she committed suicide.

What was Cleopatra's skin color?

The artifacts we have today are not numerous. They include coins minted of her that have been found at the site of Taposiris Magna in Egypt. There are a number of statues that may depict Cleopatra VII which are now located in museums scattered around the world. However, the provenance of these statues is uncertain and whether they really depict Cleopatra VII is debated.

These artifacts, and the relief at Dendera, don't tell us much about what she looked like.

Andrew Kenrick, a visiting research fellow at the University of East Anglia in the U.K., said that ancient writers usually did not discuss what ancient figures looked like. Kenrick also noted that ancient statues can be misleading. "Sculptures and statues were intended as projections of various facets of a figure, rather than intended as a true likeness," Kenrick told Live Science in an email. For instance, a sculpture may depict a ruler as being more muscular than they actually were.

Additionally, we don't know the identity of Cleopatra's mother or paternal grandmother, Kenrick noted, which means it's possible Cleopatra could have had some African descent.

"What we do know is that Cleopatra's father was Greek, and she would have considered herself to be Greek — although she did portray herself to be Egyptian, when it suited her politically," Kenrick said. At times the Ptolemies married within their own family and Cleopatra VII was married to her brother Ptolemy XIV before he was killed in 44 B.C.

However, Zahi Hawass, the former Egyptian antiquities minister, believes her Greek parentage points clearly to one answer.

"Cleopatra was not Black," Hawass said in response to Adele James, a biracial actress, being cast to play the queen in the Netflix show "Queen Cleopatra."

"As well documented history attests, she was the descendant of a Macedonian Greek general who was a contemporary of Alexander the Great. Her first language was Greek and in contemporary busts and portraits she is depicted clearly as being white," Hawass wrote in a column for Arab News at the time. Hawass did not return Live Science's request for comment at the time of publication.

Can skeletal remains reveal what Cleopatra looked like?

In 2009, the BBC aired a documentary called "Cleopatra: Portrait of a Killer" in which the documentary-makers talked to researchers examining skeletal remains found in 1926 in a tomb at Ephesus in modern-day Turkey. The researchers believed that the bones belong to Arsinoë IV, a sister of Cleopatra who was killed on the orders of Mark Antony in 41 B.C. Ancient records indicate that Cleopatra encouraged the killing, fearing that Arsinoë would try to take her throne.

Though the skull was lost during World War Two, the team reconstructed and analyzed the skull using old photographs and drawings and claimed they identified cranial features that suggest Arsinoë IV's mother was of African descent.

“The distance from the forehead to the back of the skull is long in relation to the overall height of the cranium and that is something which you see quite frequently in certain populations, one of which is ancient Egyptians and another would be Black African groups," which could suggest that Arsinoë IV had mixed ancestry, Caroline Wilkinson, an anthropology professor at the University of Liverpool, said in the documentary.

If one assumes that Arsinoë IV was Cleopatra's full sister, this would suggest the queen may have been of partly African descent, the researchers noted. However, a literature search did not reveal any published research in a scientific journal detailing these reconstructions. The researchers who made the suggestions did not return requests for comment at time of publication. And a 2021 study in the Journal of Forensic Scientists found that when forensic anthropologists tried to estimate ancestry for 251 skulls from people in the U.S. of "mixed" ancestry, they were wrong 80% of the time.

The scholars that Live Science talked to were either unaware of the claims or cautious about these findings. Duane Roller, a professor emeritus of classics at Ohio State University, said that Cleopatra and Arsinoë may not have had the same mother. The ancient writer Strabo (63 B.C. to A.D. 24), who lived in Alexandria, wrote that Ptolemy XII, the father of Cleopatra, had children through multiple mothers.

As such "we have no idea who the mother of Cleopatra and Arsinoë was, or even if they were the same person," Roller told Live Science in an email.

Skin color in the ancient world

That doesn't mean some ancient people didn't notice differences across cultural groups, Draycott said.

"The Romans commented on the white blonde and red-haired peoples in Northern Europe and the dark-skinned, 'woolly' haired people from Africa, and saw both groups as being different from themselves," Draycott said..

Romans would not have considered themselves to have white skin but rather brown or olive-toned skin, Draycott said. This can be inferred from the fact that the Romans didn't describe themselves as white but rather described people from northern Europe this way, noted Draycott.

Related stories

—Oldest human ever found in Egypt brought to life in stunning new facial approximation

—Which ancient Egyptian dynasty ruled the longest?

Kenrick said that the Greeks would also not have considered themselves to be white. “Greek should not be equated with white, as the Greeks and Romans certainly didn't consider themselves to be white” Kenrick said in an email.

Ultimately, Cleopatra's skin color isn't particularly important, Roller said.

"Cleopatra's skin color has nothing to do with her accomplishments, which are immense," Roller said.

No comments:

Post a Comment