Exploring a ‘Treasure

Trove’ of Medieval

Egyptian Recipes

A newly translated cookbook provides a tantalizing

glimpse of Cairo’s past.

THE MARKETS FOUND IN MEDIEVAL Egypt were spectacles to behold—or rather, to taste. From street vendors selling fried-pigeon snacks to streets lined with jars of foamy beer, descriptions of streets like Bayn al-Qaṣrayn can make one salivate centuries later. Now, a newly translated cookbook offers one of the only comprehensive looks at this culinary world of 14th-century Egypt.

Kanz al-Fawa’id Fi Tanwi’ al-Mawa’id, or Treasure Trove of Benefits and Variety at the Table, features 830 recipes for medieval Egyptian dishes, desserts, digestives, and even scented hand perfumes (to apply after the meal). From traditional sweet chicken dishes to desserts resembling threads of a silkworm cocoon, these recipes bring to life an important yet oft-forgotten moment in Cairene culinary history: In the 1300s, the city was a diverse, thriving metropolis known as the “mother of all nations.”

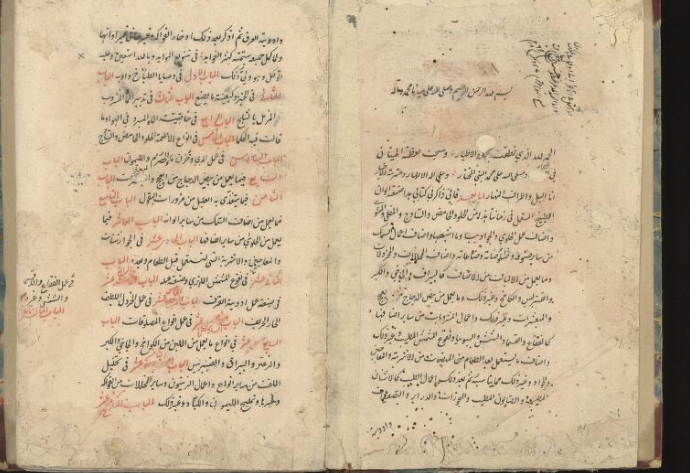

Nawal Nasrallah, who translated the Kanz into English, is an independent scholar and food writer. But her work may also qualify her as a detective. Translating the text, which had been edited in 1993, was no simple task.* The Kanz has been hand-copied many times by various scribes, many of whom may have lacked the linguistic knowledge or additional sources to properly work with the text. This left the existing cookbook ridden with miscopied words, merged recipes, and excerpts that simply didn’t make sense. By returning to the manuscript and drawing upon other contemporary resources, Nasrallah created a more comprehensive iteration of the cookbook. Her familiarity with Arabic, her native language, as well as with Middle Eastern cuisine, allowed her to see things others likely did not notice.

Nasrallah’s years of parsing through the medieval manuscripts has finally brought forth a fuller, more fleshed out Kanz—complete with an extensive introduction, glossary, and adapted recipes for the modern reader curious to recreate medieval Cairene cuisine.

Though the author of the Kanz is anonymous, Nasrallah was able to determine that the author likely drew from several specialized pamphlets for various recipes—one for fish, another for pickles, even some medical manuals from physicians—to compile the cookbook. Thanks to this anonymous author, these recipes that otherwise would have vanished have been preserved in a single source.

Extensive as it is, the Kanz offers a colorful culinary lens through which readers can glimpse into the markets, plates, and people living in a bustling, 14th-century Cairo. For instance, Nasrallah notes the abundance of fish dishes. “There are recipes for fresh (ṭarī) fish, salt-cured (māliḥ) small fish … and condiments of small crushed fishes (ṣaḥna).” Fish were popular and widely accessible, she writes, since during the Nile’s flooding season, even children could catch them. They were often consumed alongside sour ingredients and spices to aid their digestion.

Another beloved meat was pigeon—and young, ripe, plump ones at that. Known as zaghālīl, these pigeons differed from house pigeons, as they were raised in cotes located outside of the city. They could be enjoyed fried, stewed, or smothered in various sauces, or even in omelets.

Particularly intriguing, Nasrallah says, is a recipe that uses lemon juice to flavor sugar. The result is the traveler’s lemonade. By simply adding a bit of cold water, says Nasrallah, those on the move could create “something like today’s Kool-Aid.” The author of the Kanz includes several such travel provisions, which allowed traveling Egyptians to preserve food. For instance, the Kanz includes a recipe for dried mustard. “It’s prepared in a clump,” she says, “like a cookie shape, so when they’re on the road and have to grill meat, they can simply add water to create the sauce.”

Those with a sweet tooth could draw on an extensive collection of desserts and sweets. The cookbook includes a delightful array of somewhat playful recipes, ranging from “sandwich cookies … named chanteuses’ cheeks,” to “dainty cookies shaped like breasts … called virgins’ breasts.”

Stretching beyond food, the Kanz includes medicinal foods (meant to aid conditions such as mild lethargy or indigestion), recipes for distilled perfume waters, and even a bit of magic. “Surprise your master,” one recipe reads, according to Nasrallah, “with a plate of lusciously ripe fruits with verses inscribed in green and you will be in his good graces.”

One of the most notable aspects of the Kanz is its flexibility. Though likely intended for middle and upper class diners—specifically those who could afford a kitchen or even chefs of their own—it offers cheaper versions of recipes for Cairenes on a tighter budget. That flexibility extended, too, to an awareness of the varying tastes of Cairo’s unusually cosmopolitan population. One recipe for a table sauce, Nasrallah writes, noted to “add garlic if making it for a Turk; and not to add it if it is for a local person (baladī).”

In addition to translating the Kanz, Nasrallah has adapted some of the recipes for today’s cooks. She’s put together 22 modern versions, some of which appear on her blog, that swap a mortar and pestle for a food processor. And perhaps, you might try whipping up a syrupy digestive to consume after your meal, or an aromatic hand perfume so as not to continue smelling like what you’ve eaten, because, as Nasrallah notes, the Kanz isn’t simply about eating. “It’s the whole experience,” she says. “It doesn’t only cater to the stomach but also the whole well-being of the body.”

*Correction: This post previously misattributed the merged recipes and mistranslations in the Kanz to a 1993 English translation. They are predominantly due to inaccuracies that arose from the process of copying the manuscript by hand; the 1993 version is an edited text.

No comments:

Post a Comment