In 1590, Starving

Parisians Ground

Human Bones

Into Bread

During a siege, desperation drove people to disinter skeletons

from cemeteries.

IN THE DAYS LEADING UP to the French Revolution, Paris was starving. Consecutive years of poor harvests led to bread riots and widespread hunger. In response, Queen Marie-Antoinette purportedly said, “Well, if the people of Paris can’t afford bread, let them eat cake!”

She didn’t say that. In French, the former queen is credited with having said “Qu’ils mangent de la brioche,” or “Let them eat brioche.” But she didn’t say that either. It was a popular phrase to attribute to the aristocracy in the 18th century—one that Swiss philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau bandied about quite a bit. But the snappy quote was never pronounced by the queen.

It is, however, indicative of just how important bread was to the French.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, the average person in France ate somewhere between 1.5 and 2.5 pounds of bread per day. The rich also enjoyed meat and another two liters of wine each day. But for the poor, bread constituted the majority of their diet. So when wheat was scarce, the French risked starvation.

In Paris, this risk was most acute during a siege.

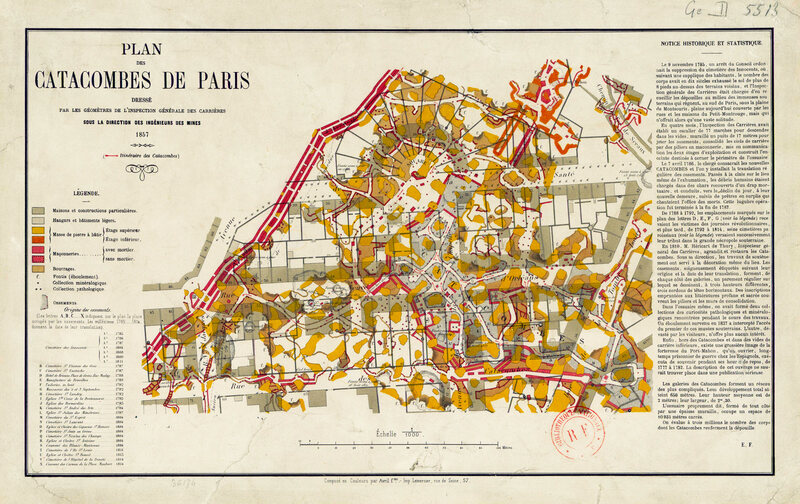

Paris has endured numerous sieges throughout its long history. The Vikings besieged the city in 845. In 1429, it was Charles VII and Joan of Arc, and in 1870, the Prussians. During these times of austerity, Parisians resorted to eating everything from military horses to street rats and zoo animals. And during one particularly problematic siege, they even ate bread made from human bones.

The road to this grisly act of baking was paved in 1589, after the death of King Henri III. His distant cousin, Henri III of Navarre, was heir to the French throne. But despite having been baptized Catholic, the King of Navarre was raised as a Protestant. At the time, France was in the throes of the Wars of Religion, a prolonged period of strife between Protestants and Catholics that lasted 36 years and took some three million lives. So it’s no surprise that Henri’s succession was far from straightforward: It took a four-year civil war against the powerful Catholic League, an anti-Protestant group allied with the Spanish Crown, for Henri to claim the throne.

After his victory against the League at the Battle of Ivry, Henri moved towards Paris. In the wake of his approaching armies, peasants deserted their lands and took refuge within the city. In time, they may have come to regret the decision.

Henri took control of several nearby towns, including Nogent-sur-Seine and Provins, endangering the Parisian food supply. Henri also had all windmills burned, essentially making it impossible for Parisians to produce bread.

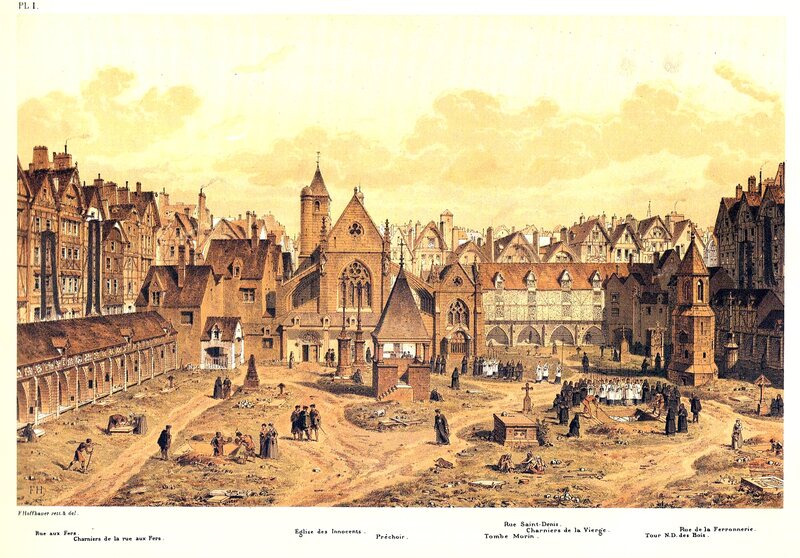

By May, Parisians were starving. The locals ate horses and mules, followed by pet dogs and cats. They then moved on to grazing on grass from parks, and finally, in August, Parisians resorted to “Madame de Montpensier’s bread.” According to an August 25, 1590, entry by Parisian diarist Pierre L’Estoile, it was made of “the bones of our forefathers” and so named because Madame de Montpensier, a powerful member of the Catholic league, “exalted its invention (without ever desiring to sample it).”

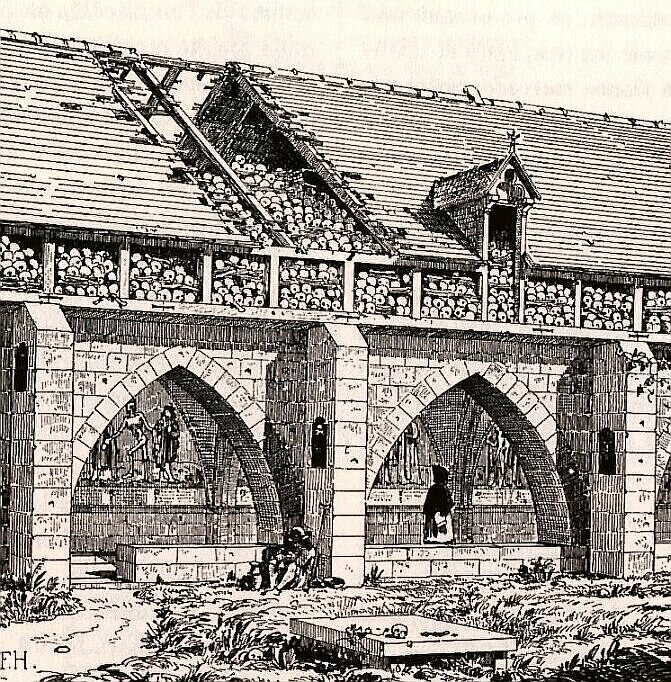

How does one make bread from one’s forefathers? Most accounts explain that the desperate poor first disinterred bones from the mass graves of the Holy Innocents Cemetery. They then ground the bones into flour and baked this flour into bread. Henrico Davilia, an Italian historian and eyewitness, described it as “vile and macabre,” an “abominable food so contagious that, the substance having come from the dead, it so increased by many the number.”

This bone flour was not exactly an ideal replacement for wheat. A lack of gluten, for example, makes it difficult for bone bread to hold together, and disinterred bones are no superfood. As Gabriel Venel wrote in his Précis de matière médicale, “The idea of reducing human bones to powder […] could only come from a mind essentially ignorant and overcome by hunger and by despair. Bones are not floury, and when they are spent by a long stay in humid soil, they contain no nourishing element.”

But even during the duress of a siege, these practical difficulties were less concerning than the image of disinterring the defunct to feed the living. “This bread,” writes Madeleine Ferrières in her Nourritures Canailles, “is bad for one simple reason: It has the taste of sacrilege and anthropology. For many, it’s the abomination of desolation.”

It’s said that the widespread starvation and resulting 40,000 to 50,000 deaths were the deciding factor for King Henri to see the error of his ways. He allowed his army to provide Parisians with food. Soon after, he lifted the siege entirely and converted to Catholicism (and, ironically, embraced the Church’s belief in transubstantiation).

“Paris,” he allegedly said of his conversion, “is well worth a Mass.”

No comments:

Post a Comment