Good morning. Here’s what you need to know to start your day.

L.A.’s deadly embrace of car-favoring traffic rules

For several years, I’ve been reporting on Los Angeles’s failure to deliver safer streets and curb traffic deaths. Despite on-paper goals to reduce the number of people killed while walking, biking and driving in the city, the death toll surged roughly 80% from 2015 to 2023.

You can probably guess how 2024 went, but here are some tragic early figures.

Preliminary data from the Los Angeles Police Department through Dec. 28 show 306 people died in crashes last year, including 170 pedestrians killed by motor vehicle drivers.

That’s a slight decline from 2023, when car crashes killed more people in L.A. than homicides did. But it marked the third straight year that more than 300 people died in crashes on city streets. More than 1,580 other crash victims were severely injured last year, virtually unchanged from 2023.

The full-year report has yet to be publicly released but is expected to be shared at a still-TBD news conference, according to LAPD’s data management division.

Why haven’t L.A. and other U.S. cities been able to stop the carnage?

We can chalk that up to a multitude of factors, including political will, driver accountability, public outreach and stronger safety regulations for automakers. But the simpler explanation is that we built our streets so drivers can go fast, which makes them more dangerous — especially for people walking.

It’s easy to normalize our car-centric world, since most of us living today were born after the automobile became a cultural necessity to get around. But the deadly street conditions we experience now were paved in large part by a century-old L.A. traffic ordinance that became the template for cities across the nation.

Today marks the 100th anniversary of that ordinance, so let’s time travel.

The origin story for L.A.’s deadly streets

Los Angeles streets in the 1920s were a far cry from the car-clogged roads we have today. Most Angelenos walked, rode bikes (and horses) and took public transportation. For many, automobiles were viewed as lethal invaders. The numbers supported the perception.

In the early 20th century, drivers were killing thousands of people each year, many of them children. That was bad news for automakers and dealers trying to sell their machines in pedestrian-rich cities that villainized their products.

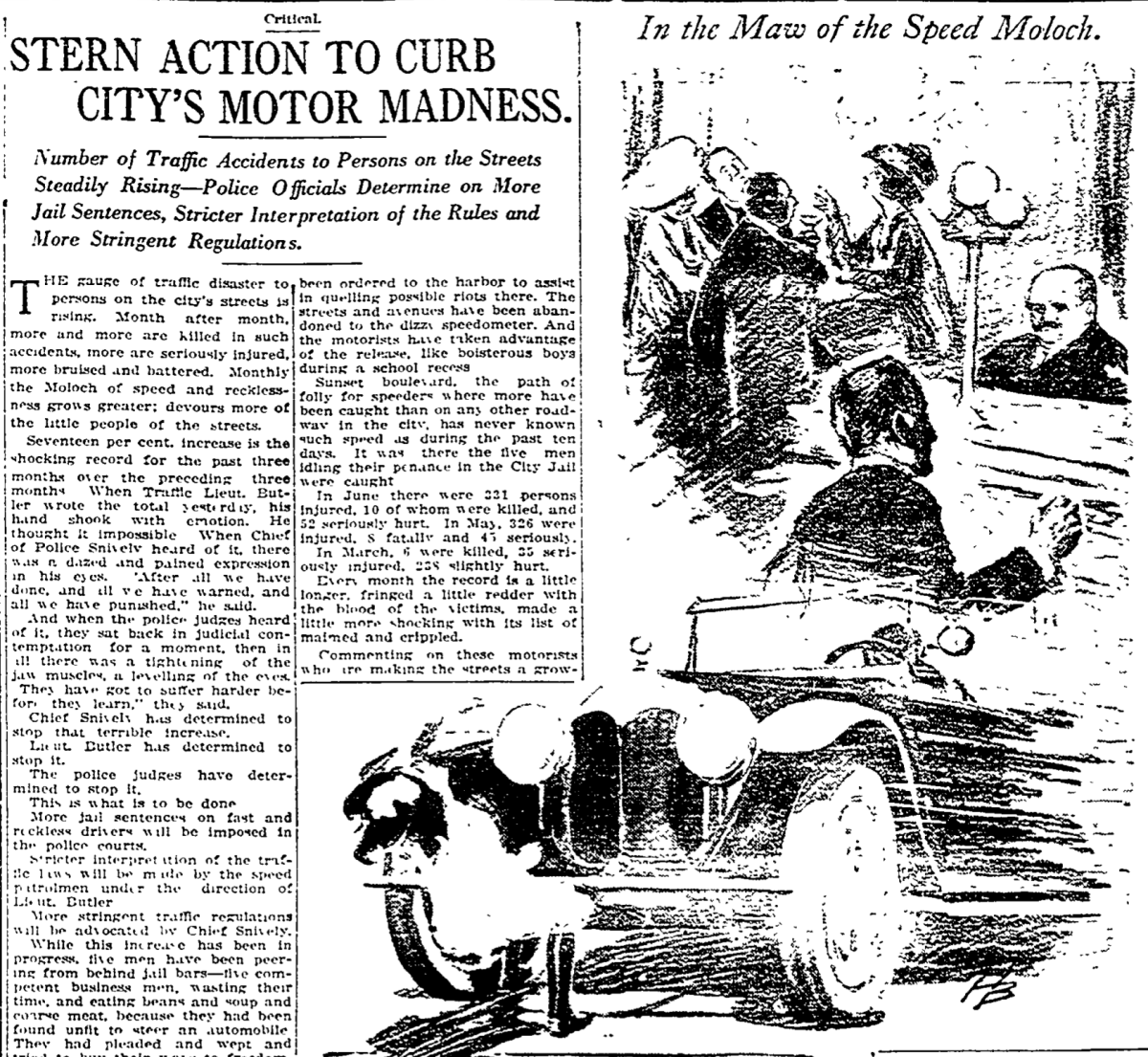

A 1916 Times article decried safety conditions on city streets, where innocent Angelenos were caught “in the maw of the Speed Moloch.” Moloch is an ancient deity to whom worshipers supposedly sacrificed their children.

(Los Angeles Times archive)

So one prominent L.A. Studebaker salesman, Paul G. Hoffman, crafted a plan: Create new traffic rules to reconfigure L.A. streets to be more car-friendly by giving drivers priority.

“What he wanted to do was find a way to make it easier to drive, to make it easier to drive faster, and also, importantly, to ensure that if a driver hit a pedestrian … the presumptive responsibility didn’t fall automatically on the driver,” tech historian Peter Norton explained.

Norton is a professor at the University of Virginia and chronicled Hoffman’s scheme in his 2008 book, “Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City.”

His body of research reveals the calculated effort by auto interests to shift the blame for traffic deaths from reckless drivers to pedestrians, clear the roads for cars and boost vehicle sales. A quick walk in your community will confirm who came out on top.

Lasting impacts

To make the car-favoring rules a reality, Hoffman recruited Miller McClintock, a Harvard PhD student who was studying motor vehicle traffic in cities. With financial support from the auto dealer, McClintock took on the role of traffic consultant and constructed the ordinance, Norton explained.

The most consequential provision, according to Norton, was that walking in the street outside of specific crossings was criminalized. That act was colloquially known as “jaywalking,” a term promoted by auto interests to shame people out of the streets that they’d had free access to for decades (“jay” is derogatory slang that essentially means a small-town idiot).

The ordinance also established that motorists were allowed to make right turns at red lights.

It was approved by the L.A. City Council in December 1924 but vetoed by Mayor George E. Cryer, a Republican, who took issue with the limitations placed on pedestrians and the safety hazards of allowing right-on-red.

“Pedestrians desiring to cross a street and who have been held up pending the release of traffic in the direction they desire to go are immediately menaced in the crossing by turning vehicles,” Cryer wrote in his veto message.

But the City Council — which Norton said was significantly influenced by auto industry interest groups — overrode his veto. The ordinance took effect on Jan. 24, 1925.

A newspaper article a few days after L.A.’s pedestrian restrictions took effect. (Los Angeles Times)

Basically, the people who stood to profit most from this technology successfully wrote the rules for how their often-lethal machines could be used in public space — and how anyone not using their products should behave as a result.

Remembering that sequence of events is important, Norton said, because it dispels the dominant narrative that car-centric streets were something a majority of Angelenos wanted.

“We forget that they didn’t dare try to get public support for the traffic ordinance of 1925,” Norton said. “The mayor was directly elected by the people of Los Angeles [and] vetoed that law. So it was not a democratic process, it was not a consumer demand process. It was a power struggle.”

Editorial cartoon published Jan. 25, 1925 critical of the ordinance’s directive to pedestrians to request the right-of-way from drivers. (Los Angeles Times)

Federal officials, also seeking to establish order on the nation’s increasingly deadly streets, took note of L.A.’s new rules.

“Rather than draft a traffic ordinance from scratch, [they] said: ‘Let’s take L.A.’s, we’ll tweak it a little bit, and it will be the official model municipal traffic ordinance of the whole country.’” Norton explained. “So wherever you are in the U.S.A. today, you’re living with a traffic ordinance that’s descended from that 1925 ordinance.”

Through lines to today

Norton noted that the ordinance was not the only factor that secured the automobile’s dominance of public space but was “symbolically and practically … the most significant” political and cultural shift in how we regulate roads and think about driver accountability.

But the new traffic laws didn’t instantly make streets safer. The Times reported in September 1925 that drivers killed more people in the roughly seven months after the ordinance took effect than in the same time period a year before.

Feature in the Sept. 20, 1925 edition of the L.A. Times. (Los Angeles Times)

L.A.’s transition to shift blame from fast drivers to pedestrians was eventually embraced on a national scale, Norton said. Pedestrians continue to bear the brunt of that normalization and battles for safer streets continue today.

California decriminalized “jaywalking” in 2022, with proponents noting that citations had been disproportionately written in communities of color.And last year, L.A. voters approved a ballot measure that requires the city to add long-planned safety upgrades for cyclists and pedestrians when it repaves streets.

For Norton, the history lesson reveals that shaking our “car-dominated status quo” is not a pipe dream.

“It’s possible to change things in ways that seem unimaginable,” he said, “and the proof of that is that L.A. did that in 1925.”

No comments:

Post a Comment