The classic Mediterranean vacation spot

that sits over a live volcano

—

Everywhere you look on Santorini, you’re reminded that you’re on a volcano. The lunar

landscapes, the black and red beaches, the pebbles made of solidified lava. The Greek

island’s transfixing beauty is a result of the area’s violent volcanic history.

Santorini is of course famous for its breathtaking crescent-shaped caldera, half of

which is submerged – making it the only sunken caldera in the world. It was created by

one of the largest known eruptions around 3,600 years ago. The explosion was so

powerful that it wrecked Santorini’s ancient city of Akrotiri and dealt a fatal blow to

the seafaring Minoan civilization, which had settled on the island at the time.

Today, Santorini – also known as Thira – is Greece’s foremost romantic playground with

luxurious villas and resorts providing pampered getaways for A-listers and dreamlike

settings for lavish weddings and photoshoots alike. The island’s steep volcanic cliffs,

perched about 1,000 feet above sea level, create an impressive geological canvas

with whitewashed houses balanced on the edge. No wonder it’s one of the most

photographed locations on the planet.

Every evening, the island comes to a grinding halt for Santorini’s world-famous sunsets.

The blue and white domed village of Oia gets packed as the golden hour draws in.

As the sun begins to set behind the caldera’s cliffs, the sky transforms into a vivid

display of red, orange, and pink hues. Thousands gasp as the last rays disappear in

the sea.

Few realize that beneath the hypnotic kaleidoscope of colors lies an active volcano.

Secrets of the deep

Santorini is part of the Hellenic Volcanic Arc, one of the most important volcanic fields

in Europe which has seen over 100 eruptions over the past 400,000 years. The East

Mediterranean’s most active underwater, and potentially dangerous, volcano, Kolumbo,

is five miles northeast of Santorini and part of the same volcanic system.

Submerged in the Aegean Sea, Kolumbo has been quiet for nearly 400 years – but it is

not asleep. The last time it erupted, in 1650, it killed 70 people and triggered a 40

foot tsunami. Strong earthquakes and aftershocks were recorded, along with toxic

gas and plumes of smoke.

Scientists know Kolumbo exploding could cause great havoc. Some of the world’s

biggest oceanographical expeditions have paid it a visit and monitoring has

increased in the last 20 years. One of the largest US research vessels, the JOIDES

Resolution deep drilling ship, traveled to Santorini for its first Mediterranean

mission between December 2022 and February 2023.

The formidable ship brought “an entire floating lab to the area,” says volcanologist

and expedition co-chief Tim Druitt. Able to drill at over 8,000 meters (26,000 feet)

beneath the surface of the sea, researchers collected previously unreached

sediments to try and reconstruct the history of volcanism in the area.

The results – initial reports are expected later this year – should help scientists not

only predict future eruptions, but also to reveal the behavior of other active

volcanoes around the world that pose a threat to millions who live in their vicinity.

The links between earthquakes and volcanoes are also being studied.

Evi Nomikou, a geological oceanographer at the University of Athens, has taken part

in every expedition on her native Santorini for the last 20 years. “We are gradually

putting together a geopuzzle [showing] which parts were [originally] land, which

parts were water,” she says.

“If we can better understand past eruptions and their impact, we have a roadmap

to better address future challenges.”

An extraterrestrial ocean

The JOIDES Resolution expedition isn’t the first major study of the area. Nomikou

says that the long-studied extreme conditions found at Kolumbo led NASA to fund

a groundbreaking expedition in 2019. “At the bottom of its crater there is an extra

-terrestrial ocean with life forms that can be found on other planets.”

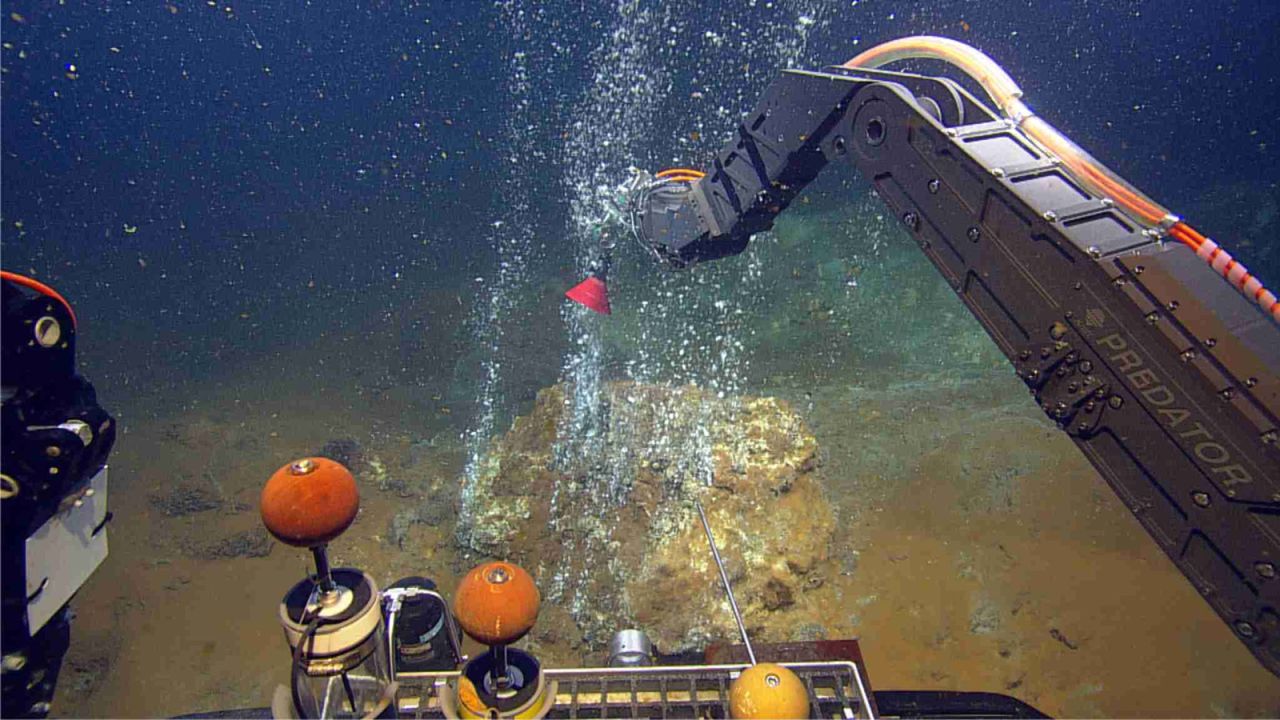

The hostile environment, with its active hydrothermal vents spewing hot water and

minerals, served as an ideal testing ground for new state-of-the-art technologies

using Autonomous Underwater Vehicles. NASA tested submersibles that one day,

it hopes, will be exploring alien oceans on moons of Jupiter and Saturn.

Another recent study also uncovered a previously undetected magma chamber

beneath Kolumbo. Scientists believe that the chamber may also be key to

understanding the seismic activity in this region.

Fuming volcanoes and bubbling craters also fired the imagination of Hollywood

producers who chose Santorini as the opening location of adrenaline-pumped 2003

Hollywood blockbuster “Lara Croft: Tomb Raider – The Cradle of Life.” Using

Santorini’s dramatic cliffs as a backdrop, Angelina Jolie found herself in hazardous

situations in mysterious waters while looking for underwater treasure.

Jolie and then-husband Brad Pitt spent vacation time on Santorini following the

shoot, and they’re not the only ones. The Kardashians, Lady Gaga and Shakira are

among the celebrities who have splashed in Santorini’s crystal-clear waters. Every

summer, mega yachts cruise back and forth between Santorini and Greece’s other

celebrity magnet, the party island of Mykonos, their VIP passengers revealing their

exclusive surroundings in glitzy posts.

Crater hikes and thermal springs

Brangelina’s romance may be over, but Lara Croft’s adventurous spirit lives on in

tourist boat excursions. They include a visit to the volcano of Nea Kameni: one of

five islands that form the Santorini volcanic complex, and a national geological park

in itself.

“The last eruption on Nea Kameni was in the 1950s,” says Marios Fytros, CEO of

travel agency Santorini View. “Visitors love the thrill of hiking up to the crater of

a volcano. It is one of our most popular excursions.” Boat tours continue with a swim

at volcanic hot springs on nearby Palea Kameni island, followed by sundowners on

deck facing Santorini’s cliffs.

Another popular tour, to the magnificent archaeological site of Akrotiri, serves as

a sober reminder of volcanic force. The thriving Bronze Age city was destroyed by

the eruption 3,600 years ago, which spewed out a nearly 20-mile high column of

ash and rock, entombing the city. Some 1,700 years later, a similar disaster would

destroy Pompeii.

With the ashes and lava removed, Akrotiri’s vividly colored frescoes today stand

beautifully preserved.

A simmering volcano

Thanks to its global fame, Santorini has seen some the biggest tourism investments

in the country. Hilton and Nobu are among the brands to have arrived on the island

in the past few years, and property prices are among the highest in Greece.

Yet geologists – who are closely monitoring Kolumbo – warn that it’s just a matter

of time before a big eruption hits again.

However, “time” in geology years can be ultra-slow. So much so that one real estate

agent on the island, who declined to be named, says that “volcanic activity never

enters the conversation” when selling a property.

When it does erupt, Kolumbo is capable of producing an eruption column tens of

miles high and is also liable to trigger a tsunami. Increased activity about 10 years

ago raised concerns but it has since subsided.

“If we start seeing increased activity in Kolumbo then we need to be alert, says

Druitt. “The good news is that volcanoes do give plenty of warning.”

Meanwhile, in 2020, Greece’s Civil Protection Agency unveiled a 185-page plan for

addressing the consequences of a possible activation of Santorini’s volcanic group.

Volcanic food and wine

In their everyday life, locals have little time to think about the volcano beyond

excursions. In summer, the island is packed. Overtourism remains one of the biggest

challenges as Santorini’s unique morphology continues to bring in the crowds. Last

year the International Union of Geological Sciences, in collaboration with UNESCO,

included the caldera of Santorini in its first list of top 100 Geological World Heritage

Beyond hotels and restaurants, all business on the island is linked to the volcano.

Locally made cosmetics are packed with minerals, and premium food ingredients

are grown in unique soil. There is a museum dedicated to the Santorini cherry tomato,

a Protected Designation of Origin product since 2006, and the island’s fava beans

are considered the best in Greece.

Then there is Santorini’s most famous export after tourism: wine. Islanders say

there’s more wine than water on Santorini.

About a fifth of the nearly 30 square mile island is taken up by vineyards, most of

which grow assyrtiko, a native grape which produces white wines that are crisp,

dry and – unsurprisingly – mineral.

The traditional “cave” houses dug into the volcanic rocks, called yposkafa, are

prime nesting grounds for honeymooners seeking their dream vacation. But for

Nomikou, who grew up on Santorini, it was Kolumbo that featured in her

childhood dreams.

“I was greatly influenced by my grandfather’s and great grandfather’s stories.

They remembered the smaller explosions at Nea Kameni,” she says.

“But they insisted that the one to worry about is ‘the one you can’t see’.”

“Gradually I realized there was another volcano, under water. A volcano more

powerful, mysterious and dangerous. It is impossible to know if any of us will

live through a big eruption but, at some point, there will be one.”

Santorini could one day be buried under a layer of ash once more. But for now –

as visitors enjoy another stunning sunset over a glass of assyrtiko – the volcano

keeps quiet.

No comments:

Post a Comment